If you’re searching for drum fills for beginners, I assume you are already familiar with the terms “beats” or “fills”.

It’s also safe to assume you already know how to play at least some of the basic drum beats aimed at beginners. If not, HERE’s my article on the subject. Give it a go and come back when you’re ready.

Anyway, before jumping into the fills, let’s talk about the difference between a drum beat, and drum fill.

A drumbeat is a rhythmic pattern, or a rhythm you repeat throughout a song. Easy, right? But what about a drum fill?

Well, a drum fill is often used as a transition between different feels or sections of a song, like, for example, when moving from a verse into a chorus. Think of them as a bridge between two different sections.

In other words, they are a temporary deviation from the beat and can be as short as half a beat or as long as multiple measures, if you fancy a solo.

As a drummer, knowing how to properly play the beat pays the bills, while fills are usually seen as a way for the drummer to show off and pull out some of his best “chops”.

On that note, knowing where to place a fill, and how long it should last is usually the easiest way to distinguish a beginner from a professional drummer.

It takes a higher level of music sensibility to know what’s the best approach, and understand that sometimes, less is more.

A good example is Ash Soan’s most recent Zildjian Live. At around the 4-and-a-half-minute mark, he could have pulled out some of his chops, but instead, decided to show you the importance of space in drum fills.

There’s a reason no day goes by without you hearing something he worked on on the radio. I guess he must be doing something right, don’t you think?

Back to our regularly scheduled program! You should focus on understanding each pattern first. Start on a practice pad and play along a click track. Once you’re comfortable enough, try it on the drum set, orchestrate it around the kit and give life to a drum fill.

To get you used to it, every drum fill has a one-measure long basic backbeat before the actual fill.

Anyway, now that we’ve learned the difference between a drum beat and a drum fill, as well as how you should approach drum fills in general, here’s some basic drum fills for beginners:

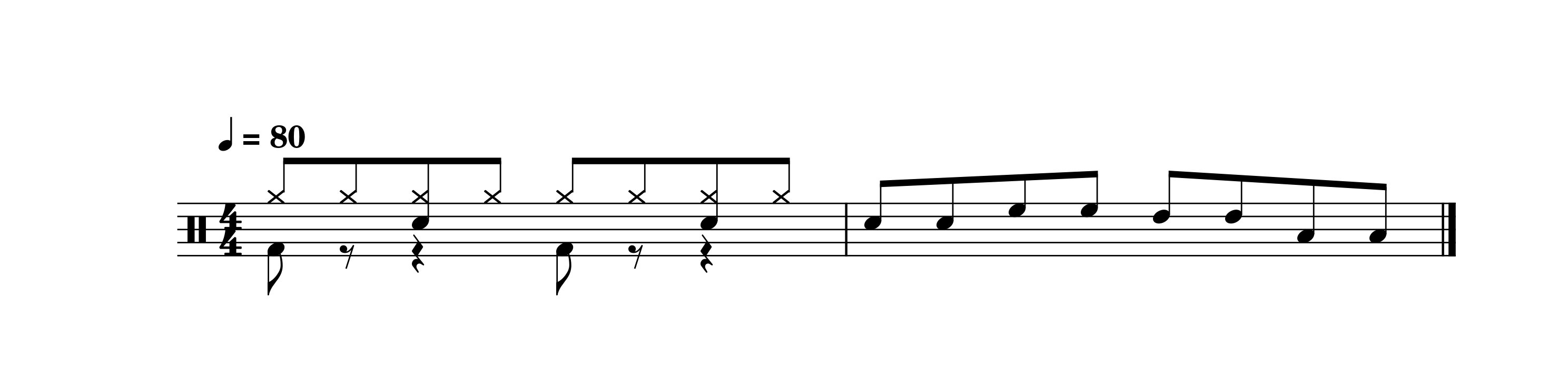

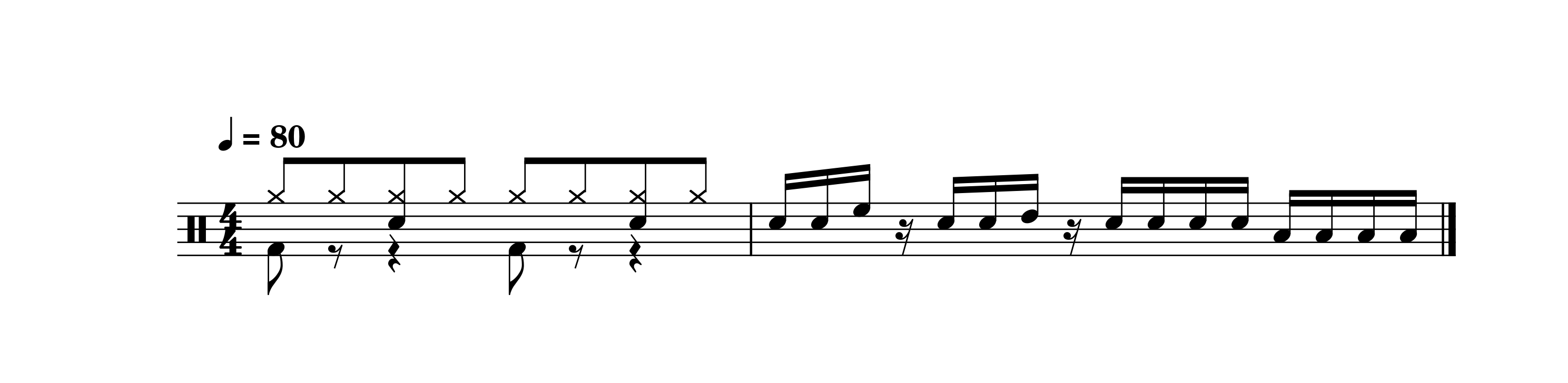

Drum Fill #1

Considering most drummer’s first drum beat is usually something based on the 8th note basic backbeat, that’s exactly what we’re using today before every single drum fill.

Considering most drummer’s first drum beat is usually something based on the 8th note basic backbeat, that’s exactly what we’re using today before every single drum fill.

Plus, the first drum fill follows the same logic, as we’re also starting with a basic 8th note drum fill.

In case you don’t know what an 8th note drum beat or fill is, take a quick look at my article on “How to Read Drum Sheet Music”.

Long story short, in a 4/4 time signature you have 4 beats per measure (top number), and each beat is represented by a quarter note (bottom number, ¼).

If we have an 8th note drum fill, and we know a quarter note represents each beat, we’ll play two 8th notes per beat, because two 8th notes equal one quarter-note.

Additionally, if we have two 8th notes per beat and each measure has 4 beats, then we’ll have a total of eight 8th notes per measure.

On top of that, the way you count an 8th note groove or fill is “one, and, two, and, three, and, four, and”.

As you can see in the drum sheet above, the first two eight notes land on the snare drum, followed by two on the first tom-tom.

Finally, you play two on the second tom-tom, and then finish it by playing another two on the floor tom.

Every single note lands on either the beat or the “and”. If that was too hard to follow, here’s what it sounds like:

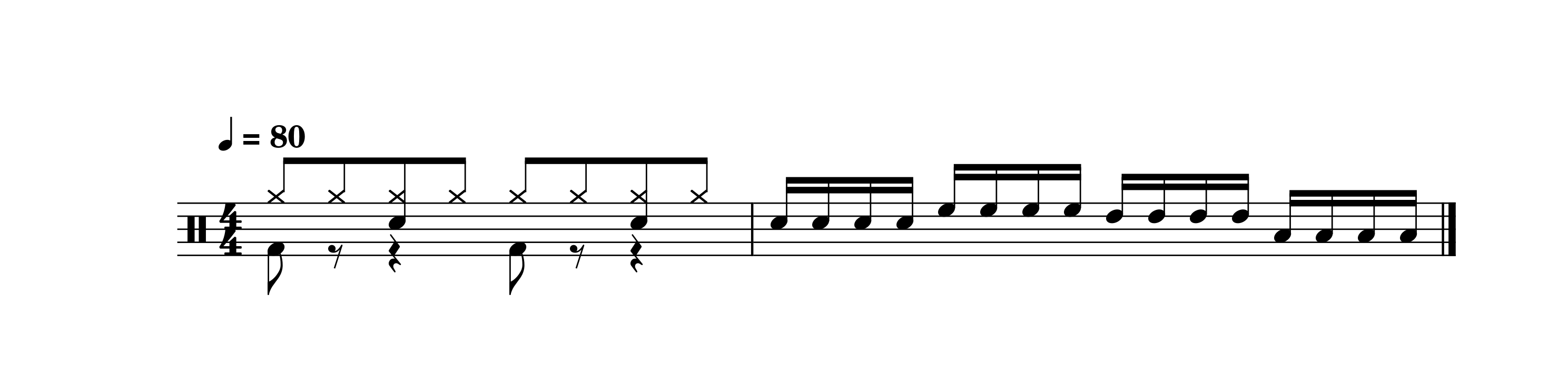

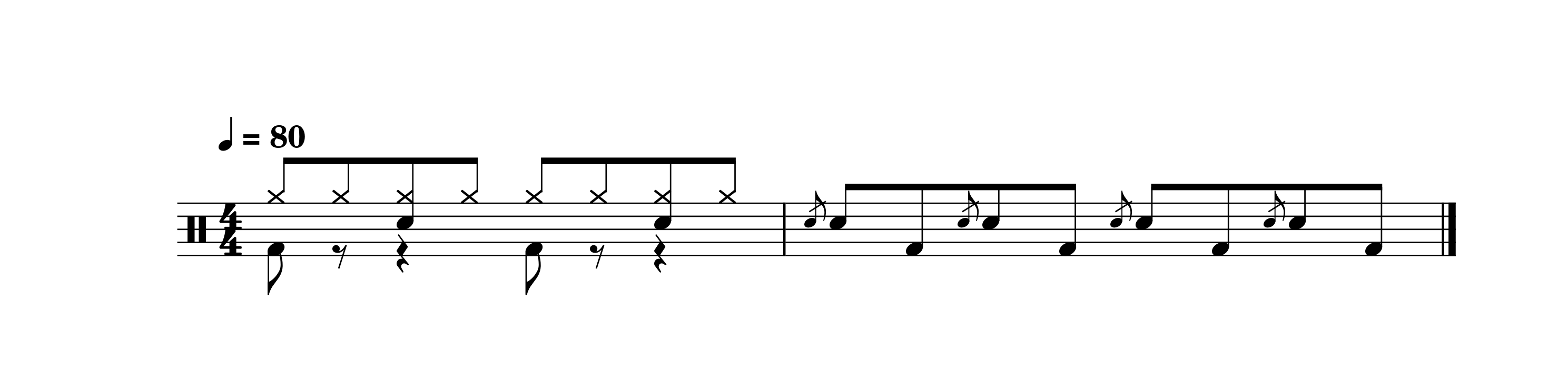

Drum Fill #2

My second suggestion is similar to the first drum fill, with a small, but important difference: it’s a 16th note drum fill, so there are twice as many notes.

My second suggestion is similar to the first drum fill, with a small, but important difference: it’s a 16th note drum fill, so there are twice as many notes.

But what does that mean? Well, as we’ve seen before, in a 4/4 time signature there are 4 beats per measure with each beat represented by a quarter note.

With that in mind, in a 16th note fill you play four notes per beat, or sixteen notes per measure because a 16th note has ¼ the value of a quarter note. Simple, right? It’s just basic math.

Unlike the 8th note drum fill, a 16th note one is counted like: “one, e, and, ah; two, e, and, ah; three, e, and, ah; four, e, and, ah”.

In our example there are no rests, so you play every single one of the 16 notes. The first four are on the snare, followed by four on the first tom-tom, four on the second tom-tom, and the last four on the floor tom.

Here’s what this 16th note drum fill sounds like:

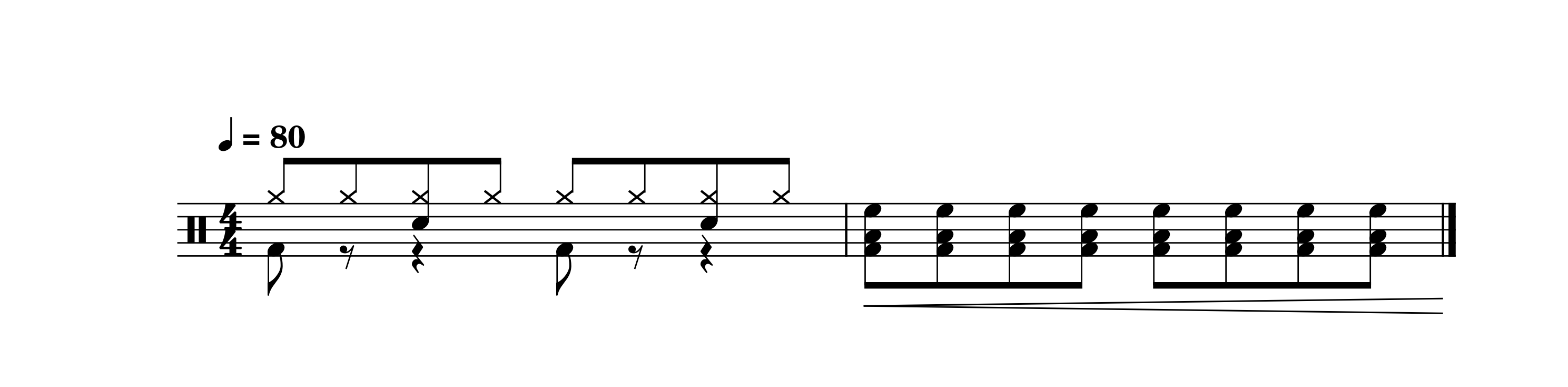

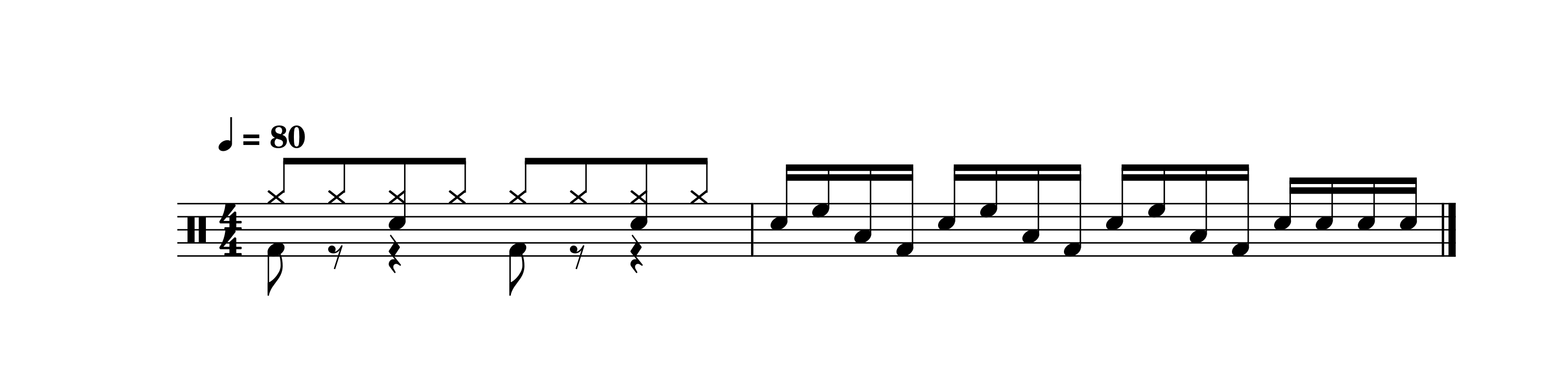

Drum Fill #3

The third drum fill is fairly simple to learn and play since it’s another 8th note drum fill and is commonly used as a build-up.

The third drum fill is fairly simple to learn and play since it’s another 8th note drum fill and is commonly used as a build-up.

If you’re someone that listens to rock often, you know exactly what type of drum fill I’m talking about.

It has a few variations, considering you can either play the snare or the first tom with your left hand. Plus, some drummers like to add the bass drum on the quarter notes or the 8th notes, while others don’t play the bass drum at all.

Since it’s played as a crescendo, you start with a lower volume and slowly get louder until the end of the measure.

If those two lines at the bottom of the measure were the other way around, you would start louder and slowly lower the volume until the end.

In our example, you play the bass drum, the floor tom using your right hand, and the first tom using your left one, at the same time.

Practice until it’s smooth enough because the main goal with this type of drum fill is to avoid any unwanted flams (which consist of a stroke preceded by a grace note).

Since it’s an 8th note drum fill in a 4/4 time signature, there are eight 8th notes per measure, as we’ve seen before.

As with any other 8th note pattern, you count it as “one, and, two, and, three, and, four, and”.

Here’s what this iconic rock drum fill sounds like:

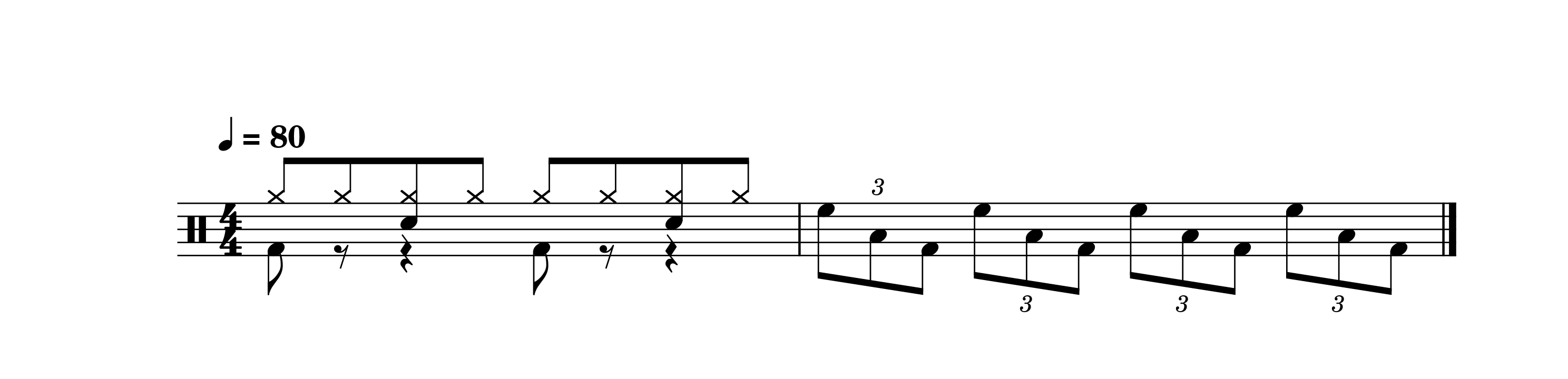

Drum Fill #4

Who doesn’t love John Bonham? Most drummers do, and anyone who doesn’t, it’s most likely because they’ve never heard of him.

Besides playing in one of the most popular rock bands in the world, Bonham was and still is, a big influence on drummers around the world.

He left behind a generous legacy, with Bonham Triplets being one of the most important parts of said legacy.

If you don’t know what a triplet is, it divides a unit of time into three equal parts. In this case, you write them using 3 8th notes per beat.

But wait, that doesn’t make any sense, does it? If it uses 3 8th notes, in a 4/4 time signature, that results in the value of one and a half counts per beat, instead of one.

Even though it’s mathematically incorrect, everything you need to know is, a triplet has the number 3 written above and their 3 8th notes together have the same value of 2 regular 8th notes or one quarter-note.

The way most people count an 8th note triplet is “one-trip-let, two-trip-let, three-trip-let, four-trip-let”.

A simplified version of Bonham’s famous triplet is something like this: on the beat, hit the first tom with your left hand. Then, on the “trip-“ strike the floor tom, as well as the bass drum on the “-let”.

Since one 8th note triplet has the same value as a quarter note, and in a 4/4 time signature, there are 4 quarter notes per measure, repeat the triplet a total of four times.

That’s it, you just found your inner John Bonham. If you’re curious, here’s what these triplets sound like:

Drum Fill #5

To add a little bit more flavor to these drum fills, we are including rests in this one because they are just as important as notes.

This drum fill in particular is similar to the second one since it’s also a 16th note one counted as “one, e, and, ah; two, e, and, ah”, and so on.

The main difference is the fact that on the “ah” of the first and second beat there’s a rest.

In other words, you won’t play anything for the duration of that rest, which in this case is a 16th note rest.

On the first beat, you hit the snare drum on the “one” and the “e”, as well as the first tom on the “and”.

The second beat is just like the first one, except for the tom you hit, which in this case is the second one.

On top of that, the second half of the drum fill is also mirrored, in the sense that you hit the snare drum 4 times in beat 3, and do the same on the floor tom in beat 4.

Here’s what the fifth drum fill sounds like:

Drum Fill #6

After including some rests and trying signature fills, it’s now time to apply drum rudiments to a fill. To be honest, there’s no better rudiment to start with than the flam.

After including some rests and trying signature fills, it’s now time to apply drum rudiments to a fill. To be honest, there’s no better rudiment to start with than the flam.

If with the 3rd drum fill the point was to avoid unwanted flams, now you need to make a conscious effort to play them as smooth as possible.

If you still don’t know the definition of a flam, it’s a drum rudiment where a drummer strikes a grace note just a split second before striking the primary stroke.

To keep things simple, this is another 8th note drum fill and all you need is your snare and bass drum.

It’s safe to assume you know by now how to count an 8th note drum fill. To summarize this drum fill, you strike the snare drum every single beat, and the bass drum every “and”.

On top of that, every time you hit the snare drum you should play a flam, instead of a regular note.

As a good exercise to develop your creativity and flow, try adding flams to any of the previous drum fills.

To conclude, here’s what the sixth fill sounds like:

Drum Fill #7

As far as drum fills for beginners go, this is one of the most fun to play and surely something you’ll use further down the road.

As far as drum fills for beginners go, this is one of the most fun to play and surely something you’ll use further down the road.

This is another 16th note drum fill with no rests, but with a few bass drum notes in the middle.

It’s based on a popular linear sticking pattern, the R L R K. Linear simply means that no two limbs are played simultaneously. Plus, the letters represent your right hand, your left hand, and the kick.

In other words, the pattern is Right, Left, Right, Kick, played as 16th notes. The first note is played on the snare drum, the second one is on the first tom and the third on the floor tom, follow by the kick drum.

Since the pattern equals 4 16th notes, which is the same as a quarter note, and in a 4/4 time signature there are 4 quarter notes, you could repeat the pattern a total of 4 times.

Still, to make things more interesting, we only repeat it 3 times instead. Why 3 times? Well, because I like to finish it differently, and in this case, with 4 16th notes on the snare drum.

Don’t forget to count 16th notes as we’ve seen before, and practice the R L R K slowly until it becomes second nature.

If you put everything together, here’s what this useful linear drum fill sounds like:

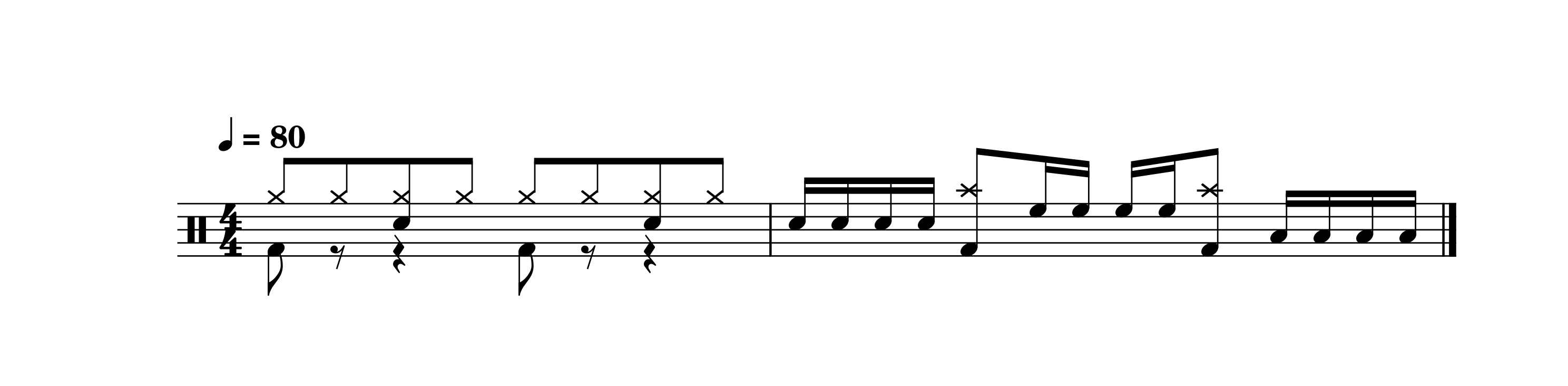

Drum Fill #8

Another fun thing you can do to spice up your drum fills that we haven’t done yet, is to add cymbals to create accents.

Another fun thing you can do to spice up your drum fills that we haven’t done yet, is to add cymbals to create accents.

The last drum fill is yet again, another 16h note one. Remember to count the 16th notes as “one, e, and, ah; two, e, and, ah;” etc.

Let’s start with the first and the last group of 16th notes since they’re by far the easiest part of the whole drum fill.

The first group of 4 16th notes is played on the snare drum, while the last group is played on the floor tom.

The middle part is where things get tricky, so let’s learn it step by step. First, on the second beat, you hit a crash of your choice and the bass drum simultaneously.

In a 4/4 time signature, as we’ve seen many times before, each beat is represented by a quarter note and there’s a total of 4 per measure.

With that in mind, both the crash and the bass drum hits are notated as 8th notes, which means they last for half a beat since there are two 8th notes per beat (or a quarter note each).

That means when counting out loud, you hit them on the “two” and on the “e” you do nothing at all.

Then, you strike your first tom on the “and” and the “ah” of the second beat, as well as on the “three” and “e” of the third beat.

After that, there’s a “16th note pause”, so you don’t do anything on the “and” of the third beat either, and you finish it by hitting the bass drum and the crash simultaneously on the “ah” of the third beat.

To help you understand what you’re playing, here’s what this drum fill sounds like:

Conclusion

Well, you did it! You learned your first drum fills, and I’m pretty sure you’re just as excited as I was back in the day.

Remember to always practice as slow as possible and increase the speed only when you’re comfortable enough to play them smoothly.

As an exercise, you can always mix and match the different fills to create different patterns and develop your drumming skills even further.

Another thing you can do is start the fills with your non-dominant hand because as drummers, it’s important to be confident with any of our limbs.

To develop your sense of rhythm, make sure to always practice with a metronome. Not only does it help keep track of your progress, being able to play with a metronome is a must for any drummer.

Building muscle memory takes time, so avoid any shortcuts, respect any nuances like the flams and the rests, and progress as slow as you need to avoid sloppiness.

Make sure you enjoy the process and have fun incorporating them into your drumming vocabulary.

In the end, I hope this article achieved its main purpose of providing your first drum fills for beginners.